In the recent past, Malta has once again become the nesting place for a rising number of mother turtles. Many species have been spotted in Maltese waters such as the Hawksbill, Kemp’s Ridley, Green turtles as well as the occasional beached leatherback. The largest of the hard-shelled turtles, reaching up to 100 cm in length, the Loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) also referred to as ‘fekruna komuni’ or the common turtle, is the species that is a regular visitor on our sandy shores. Nesting mothers typically return to the same beach they once emerged from, despite the lengthy travel, often covering up to 13,000 km in one year. Their young will also make the same journey, keeping the best nesting spots in the family. Turtles are typically considered slow-sebastians on land, however, they are very much speedy-stevens in water. Through GPS tracking of post-released loggerheads here in Malta, speed ranges were determined between 2.4 and 8km/h.

Nest sites around the Maltese islands

The following infographic (Figure 1) shows the several nesting sites where nests have been more or less successful, during the year 2020. Commonly frequented beaches are typically Ghadira Bay, Golden Sands, Gnejna Bay and Ramla Bay in Gozo. This year in particular, was considered quite a good year for hatchling success, about 64% survival overall, as the general public was hidden away behind closed doors due to the Covid-19 lockdown enforcements. The less frequented beaches meant that there were less obstructions and disturbances in the path of the nesting turtles and later, the emerging hatchlings.

Figure 1: Infographic on nest survival rates for turtle hatchlings around the Maltese islands during the year 2020.

Nesting Season

This is typically between the middle of May to the middle of August for loggerheads. July is considered the peak month during nesting season in Malta, based on more than a decade’s worth of data. More than one clutch can be laid in one season; however, this does not happen annually but biennially, some laying more than one clutch one year but then only one clutch the following year. A Loggerhead clutch can contain between 80 to 120 eggs at a time. These little ones incubate for 50 to 60 days to later hatch between the middle of July and middle of October. Temperature is the determining factor for the sex of the hatchlings, this is called ‘Temperature Dependent Sex Determination’ (TSD). Temperatures exceeding 29 degrees Celsius will become females, whereas temperatures under 29 degrees Celsius typically become males. Sex determination normally occurs between day 20 and 30 of the incubation period. Marine biologists and turtle enthusiasts alike often use the saying ‘Cool dudes and hot chicks’ to remember how warmer nest temperatures produce more females and cooler temperatures result in more male hatchlings. Since temperatures dictate the sex ratios of nests, global warming is considered a major threat, particularly since high nest temperatures produce more females than males and hence disrupting the natural ratio during incubation.

Why should we protect sea turtles?

First and foremost, sea turtles are considered a ‘keystone species’, they are important for both coastal ecosystems on land as well as marine ones, and the other species that depend on them. They are responsible for grazing on seagrass, controlling as well as promoting new growth, whilst also feeding on the less charismatic species- the jellyfish, other invertebrates as well as shelled organisms like crabs. By controlling jellyfish populations, us swimmers, snorkelers, and divers alike, swim with a bit more ease and a little less stinging! Through digestion of these invertebrates and shelled organisms, they also provide food sources for other species to feed on, providing them with nutrients like calcium.

Secondly, nesting is very often not a 100% successful, hence why the high quantities of eggs laid in a clutch. Different factors might result in unhatched, unfertilized, abnormal, bacteria ridden eggs, etc. Remnant empty eggshells as well as unhatched ones provide important nutrients for the beach.

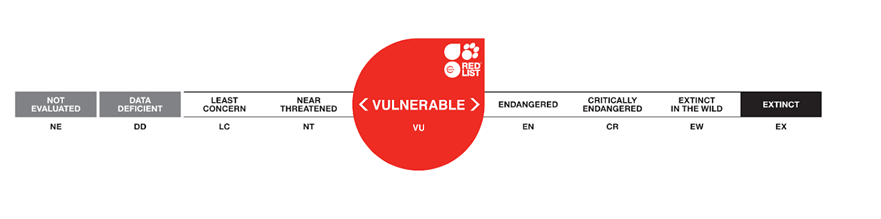

All in all, they are a very important species and are facing an assortment of threats at present including fishing pressures,tourism and recreation, noise, light and mostly plastic pollution. They are currently listed as ‘Vulnerable’ on the IUCN Red list for endangered species.

What to do if you encounter a turtle or hatchlings?

The DOs and the definite DONTs

1. We urge you to fight the impulse to post to your socials first. Social media is like wildfire and word spreads quickly, if crowds form around the nesting mother this might cause unnecessary noise and stress, causing the animal to abandon nesting or abort her young. The same goes for glaring screens and the use of torches or bright lights. Any beach goers within the vicinity of a turtle are urged to refrain from using bright lights, substituting for red light/ red filters on flashlights instead so as not to cause any disturbance. Think of how annoying it is when someone checks their phone during a film at the cinema!

2. Do not be an obstruction and do not cause an obstruction. Any onlookers are able to observe at a safe distance as long as they are out of the vicinity of the animal.

3. Shhhhh! It is crucial to keep quiet so as not to cause any disturbance or overwhelm the turtle. You are also allowed to enthusiastically shush people around you.

4. It is absolutely crucial that you do not interfere with the hatchlings’ journey to the sea. During this time the little ones imprint on the beach they have just nested on, in order to make their way back to have a nest of themselves. Any interference would disrupt this important process.

5. Just as important, is to not interfere, touch eggs or put any objects inside the nesting chamber. Any chemicals like insect repellent or sunscreen as well as other chemicals might introduce bacteria and affect the general health of the eggs. Any movement to the eggs also might disrupt the normal hatching process.

6. Do not pick up hatchlings, they can be guided without being touched if necessary, by knowledgeable team members. Hatchlings have small food reserves that can provide them with up to 3 days of energy, any mishandling may easily rupture these pocket reserves.

7. Do not litter. Plastic pollution is a big threat to turtles. They can entrap or obstruct little hatchlings and prevent them from reaching the water. Adult turtles can mistake any floating plastic objects for jellyfish, causing all sorts of problems such as suffocation.

8. Any sandcastles or sand pits made during the day can also entrap hatchlings or obstruct their way. As lovely as your sandcastle may be, take a picture and please flatten the sand so as to let nature take its course. Any sand pits can be easily filled and flattened, think of it as your small contribution in helping the process.

9. Report any beached, injured, or entangled animals. The public is urged not to attempt removing any entanglement themselves as this might be removed badly. Please contact the ‘Wildlife Rescue’ number on 99999505, for a member of the team to make an educated decision.

10. Lastly, any boat owners or fisherman are kindly asked to be mindful of any surface swimmers in their vicinity. Speeding boats have caused many collisions with wildlife, of which may have had to be admitted to a rehabilitation centre until healthy enough for a release. Fishing lines and hooks should not be thrown in the sea and disposed of safely, this is also keeping in mind seabathers and other creatures.

Like a single drop in the ocean, every small act of kindness and contribution has the power to shape a larger, more compassionate world. As guardians of this precious planet, it is our sacred duty to protect and cherish nature’s delicate balance, to shield it from harm and to mend the wounds we may have unintentionally inflicted.

References:

Nature Trust -FEE Malta, Turtle Nest Patrolling and Guarding Manual

Cutajar, M., Ferlat, C., Attard, V. and Gruppetta, A., 2022. Tracking Caretta caretta: movement patterns following rehabilitation in Malta. Xjenza Online, 10(2), pp.2-14.